![]()

NBC’s Rokerthon

Speed is key for artist Chris Hengeveld.

For Flame artist Chris Hengeveld of Northern Lights in New York City, high-performance file-level storage and a Fibre Channel connection mean it’s never been easier for him to download original source footage and share reference files with editorial on another floor. But Hengeveld still does 80 percent of his work the old-fashioned way: off hand-delivered drives that come in with raw footage from production.

Chris Hengeveld

The bicoastal editorial and finishing facility Northern Lights — parent company to motion graphics house Mr. Wonderful, the audio facility SuperExploder and production boutique Bodega — has an enviably symbiotic relationship with its various divisions. “We’re a small company but can go where we need to go,” says colorist/compositor Hengeveld. “We also help each other out. I do a lot of compositing, and Mr. Wonderful might be able to help me out or an assistant editor here might help me with After Effects work. There’s a lot of spillover between the companies, and I think that’s why we stay busy.”

Hengeveld, who has been with Northern Lights for nine years, uses Flame Premium, Autodesk’s visual effects finishing bundle of Flame and Flare with grading software Lustre. “It lets me do everything from final color work, VFX and compositing to plain-old finishing to get it out of the box and onto the air,” he says. With Northern Lights’ TV-centric work now including a growing cache of Web content, Hengeveld must often grade and finish in parallel. “No matter how you send it out, chances are what you’ve done is going to make it to the Web in some way. We make sure that what we make look good on TV also looks good on the Web. It’s often just two different outputs. What looks good on broadcast you often have to goose a bit to get it to look good on the Web. Also, the audio specs are slightly different.”

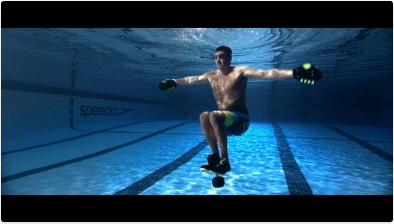

Hengeveld provided compositing and color on this spot for Speedo.

Editorial workflows typically begin on the floor above Hengeveld in Avid, “and an increasing number, as time goes by, in Adobe Premiere,” he says. Editors are connected to media through a TerraBlock shared storage system from Facilis. “Each room works off a partition from the TerraBlock, though typically with files transcoded from the original footage,” he says. “There’s very little that gets translated from them to me, in terms of clip-based material. But we do have an Aurora RAID from Rorke (now Scale Logic) off which we run a HyperFS SAN — a very high-performance, file-level storage area network — that connects to all the rooms and lets us share material very easily.”

The Avids in editorial at Northern Lights are connected by Gigabit Ethernet, but Hengeveld’s room is connected by Fibre. “I get very fast downloading of whatever I need. That system includes Mr. Wonderful, too, so we can share what we need to, when we need to. But I don’t really share much of the Avid work except for reference files.” For that, he goes back to raw camera footage. “I’d say bout 80 percent of the time, I’m pulling that raw shoot material off of G-Technology drives. It’s still sneaker-net on getting those source drives, and I don’t think that’s ever going to change,” he says. “I sometimes get 6TB of footage in for certain jobs and you’re not going to copy that all to a centrally located storage, especially when you’ll end up using about a hundredth of that material.”

The source drives are typically dupes from the production company, which more often than not is sister company Bodega. “These drives are not made for permanent storage,” he says. “These are transitional drives. But if you’re storing stuff that you want to access in five to six years, it’s really got to go to LTO or some other system.” It’s another reason he’s so committed to Flame and Lustre, he says. Both archive every project locally with its complete media, which can be then be easily dropped onto an LTO for safe long-term storage.

Time or money constraints can shift this basic workflow for Hengeveld, who sometimes receives a piece of a project from an editor that has been stripped of its color correction. “In that case, instead of loading in the raw material, I would load in the 15- or 30-second clip that they’ve created and work off of that. The downside with that is if the clip was shot with an adjustable format camera like a Red or Arri RAW, I lose that control. But at least, if they shoot it in Log-C, I still have the ability to have material that has a lot of latitude to work with. It’s not desirable, but for better stuff I almost always go back to the original source material and do a conform. But you sometimes are forced to make concessions, depending on how much time or budget the client has.”

A recent spot for IZod, with color by Hengeveld.

Those same constraints, paired with advances in technology, also mean far fewer in-person client meetings. “So much of this stuff is being evaluated on their computer after I’ve done a grade or composite on it,” he says. “I guess they feel more trust with the companies they’re working with. And let’s be honest: when you get into these very detailed composites, it can be like watching paint dry. Yet, many times when I’m grading, I love having a client here because I think the sum of two is always greater than one. I enjoy the interaction. I learn something and I get to know my client better, too. I find out more about their subjectivity and what they like. There’s a lot to be said for it.”

Hengeveld also knows that his clients can often be more efficient at their own offices, especially when handling multiple projects at once, influencing their preferences for virtual meetings. “That’s the reality. There’s good and bad about that trade off. But sometimes, nothing beats an in-person session.”

Check out the original article HERE.